Rabbit Rabbit #13: The Land of Oz

The Comforting Magnetism of Australian cinema

The cast of The Castle

In Rob Sitch’s 1997 film The Castle, a young man named Dale Kerrigan lives with his family in a modest house directly next to the bustling Tullamarine Airport in Melbourne. Planes taxi outside his bedroom window and fly overheard ceaselessly. But for the Kerrigans, this is not a problem; it’s an asset. Early in the film, when his sister and her husband return from their honeymoon, Dale explains in a chipper voiceover, “Grace and Con had a great honeymoon in Thailand. We met ‘em as they came off the plane to the baggage cart, which was lucky ‘cause they had heaps of stuff. We couldn’t wait to hear all the stories about their trip, and we didn’t have to wait that long either, ‘cause one of the good things about living next to the airport is that it doesn’t take long to walk home!” The bright-side mentality is astoundingly funny and touching.

I love Australia. Most people who know me know it. In fact, I’m convinced I was Australian in another life. I get excited whenever Australia comes up in conversation. I am always the first to identify a person’s Australian accent and can do a near-perfect one myself (sorry.) There is no other country to which I feel so soulfully tethered despite having zero traceable lineage to it. I’ve never been, and have no reason to call it superior other than it just seems awesome there.

My enthusiasm primarily has to do with the homespun appeal of Australian cinema, namely the kitsch dramedies of the 1990s (The Castle is consistently the highest ranked), which came as a result of efforts made in collaboration between the government and arts and cultural commissions to promote Australian national identity and history via stories of family, community, and personal strength. Unbeknownst to many, though, I had personal ties to the country years before these films entered my life.

In 2015, I was a freshman in high school taking a required class called “computer applications.” Notoriously the most boring joke of a class at school, comp apps was greenlit to help us early high-schoolers hone our skills in Microsoft Office Suites. The course was taught by a begrudged veteran of the IT department who seemed to care less about our mastering Excel shortcuts than we did. He assigned us tasks that, when approached with minimal efficiency and precision, could easily be finished with thirty minutes left to spare in the period, leaving room to get a jumpstart on homework or, for myself and my two seatmates, go on Google Earth.

To pass the time one afternoon, I conceived of a game for us: we’d close our eyes, zoom in on the massive desktop screen, and click on a location to explore in extreme depth using Streetview. We landed on Glebe, an inner-Western suburb in New South Wales, just outside of Sydney. For the next few months, we spent our free time traversing the streets of Glebe, acquainting ourselves with the local businesses, including our favorite corner pub, Mr. Falcon’s. Google Earth even had a feature that allowed us to go inside the pub and see patrons frozen in time, drinking and dancing to live music. I loved that I could virtually walk around this village so far away from me and see how life unfolded there. It was sort of like an endless movie. My version of escapism during the school day.

Mr. Falcon’s

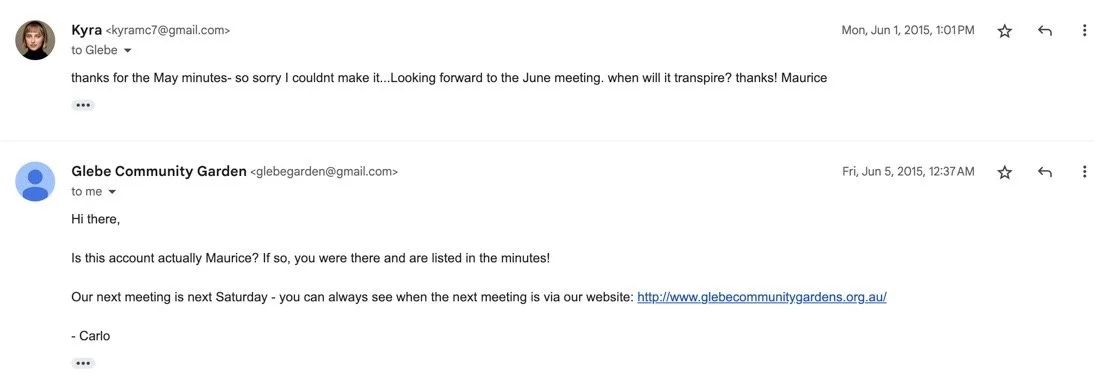

Naturally, I took it too far. When we came across the Glebe Community Garden, which linked us to a weekly newsletter, I immediately subscribed and took on the false identity of Maurice, a Garden board member. Sometimes I replied to the newsletter, pretending to be out of town for meetings, swearing I’d be there next time. Twice the president, a bloke named Carlo who by no fault of his own found himself at the mercy of my half-baked adolescent schemes across the globe, responded.

Poor Carlo.

Carlo first apologizes (unnecessarily, might I add) before admitting he has “no idea” who I am. Then, he is clearly confused as to why his board member listed as present in the meeting notes now claims he was absent. However, he chooses to gently inquire if this is “actually Maurice,” even though I neglected to delete my custom signature with a theater emoji. I think it’s safe to say he knew it wasn’t Maurice, and not just because the word “transpire” is a dead giveaway. He then proceeds to kindly remind me when the next meeting is and shares a link to the calendar. Good on you, Carlo.

For a few years, I saw my Glebe adventures as a mere silly story of the past. That is until I fell in love with Australian cinema early in the pandemic. It began with P.J. Hogan’s 1994 romp Muriel’s Wedding starring the inimitable Toni Collette, which I’ve now seen upwards of twenty times. I then watched her earlier, lesser-known independent Australian films, including Cosi, which follows a group of patients at a mental hospital as they prepare to put on a production of the opera Cosi Fan Tutte, and Spotswood, which sealed the deal for me on this little pocket of the cinematic world

Like all genre films, there is a loose formula these movies follow. Typically, they take place in a suburb located just outside a major city, usually Sydney or Melbourne, and tend to focus on a tight-knit community of people ranging from a town to a workplace or a family unit. These people are almost always working class, facing challenges regarding money and autonomy over their livelihoods. But most importantly, they fight for the right to experience joy and freedom together as a community.

Spotswood, which I recently rewatched to prepare for this newsletter, stars Anthony Hopkins as Errol Wallace, a business financial consultant assigned to help Balls, a small moccasin factory in the fictional Melbourne suburb of Spotswood increase efficiency and productivity in the workplace and faltering economic market. As the film begins, we are introduced to the eccentric employees of Balls Factory. Wendy and Carey, the two youngest, bike to work laughing and squawking at pigeons. Gordon, a longtime employee, hums the tune to Sinatra’s “Who Wants to be a Millionaire?” (Famously, the answer is “I don’t!”). He then gives Mr. Wallace directions to Mr. Ball’s office. “Now what would be your most direct route?” he ponders aloud. “Down this corridor, then left after your third door.” Mr. Wallace thanks him and begins to leave, but Gordon continues: “You’ll find two passages: one on your left, one on your right. Ignore them: they’re not the ones you want. Your best bet would be the very next one on the right…or would it?”

Ben Mendelsohn and Toni Collette as Wendy and Carey in Spotswood

Wallace becomes concerned right away. Clearly, this is not an efficient company. No one at Balls is looking to cut corners. The factory is a labyrinthine funhouse; at every turn sits another smiling employee, ready to chat for a few minutes about this and that before returning to work. Lunch hour is akin to a celebratory gathering, and the telecom system serves as an easy way to ring up the sewing department midway through the morning shift just to say ‘hi.’ This seemingly slacker behavior, however, is not at all nefarious. It would be criminal to call it anything but endearing. They just enjoy one another’s company that much.

One look at the financial records and Mr. Wallace knows the group is in peril. Mr. Ball, the company’s saintly, grandfatherly founder, has been secretly selling off his own assets for years to keep the business afloat and protect his employees from environmental changes, pay cuts, or god forbid layoffs. Ball just can’t bear to let them down, despite the imminence of bankruptcy.

Even though his high-brow job demands that he look past it, Wallace ultimately cannot fight the kindness of the Spotswood community. When union picketers vandalize his car and pop his tires, a group of Ball employees fix it up and give it a new paint job. Gordon invites Mr. Wallace to join their team in a local slot car racing competition, which he reluctantly attends and ends up winning the championship. Wallace quits his corporate job and signs on to work for Mr. Ball as a fellow shareholder in the company alongside all its employees.

There is a warmth and earnestness of character at the heart Spotswood. It is a pro-labor and pro-union movie that celebrates the small community and unabashedly supports any working citizen who stands up to those above them in a position of power. I would venture to call it a leftist film. This earnestness of character is present in all Australian comedies, and when combined with a situation that is supposed to be serious, hilarity ensues. We cannot help but laugh at the Kerrigan family’s enthusiasm for living next to the airport, or Muriel Heslop’s delight at the prospect of cashing in a blank check to take herself on holiday (release the Aussie slang!) to the trashy Hibiscus Island. These movies aren’t preachy or didactic about seeing the world in a certain way, which is what makes them so universally comforting. They simply refuse to reject hope, an action that in and of itself soothes the soul.

So perhaps my stint as a fake citizen of Glebe was really my foray into understanding the nature of Australian people as reflected onscreen in their incredible and beloved films. If Carlo and his garden gang being swindled by an adoring American high schooler had been brought to the attention of the Film Finance Corporation Australia, I bet they’d have commissioned it for production immediately. We simply cannot help but root for characters to whom joy comes easily. Of course, we know that in real life, things don’t always work out that way. The little guy does not always win. But Australian comedies make us wonder why they the heck they shouldn’t, and how joyous it feels when they do. For that, I’ll watch them again and again and again.

P.S. Recommendations (Australian-themed): The Seekers, an Australian folk group that topped the charts in the ‘60s. I highly recommend this patriotic song. Saturday Quiz Show, a comedy podcast hosted by John Leary. This episode in particular features Sarah Snook and her hilarious husband, Dave Lawson. Another great flick of the ‘90s I didn’t mention: Baz Luhrmann’s Strictly Ballroom.