Rabbit Rabbit #14: Everybody Loves a Melodrama

Private & Public Modes of Storytelling in Todd Haynes’ May December

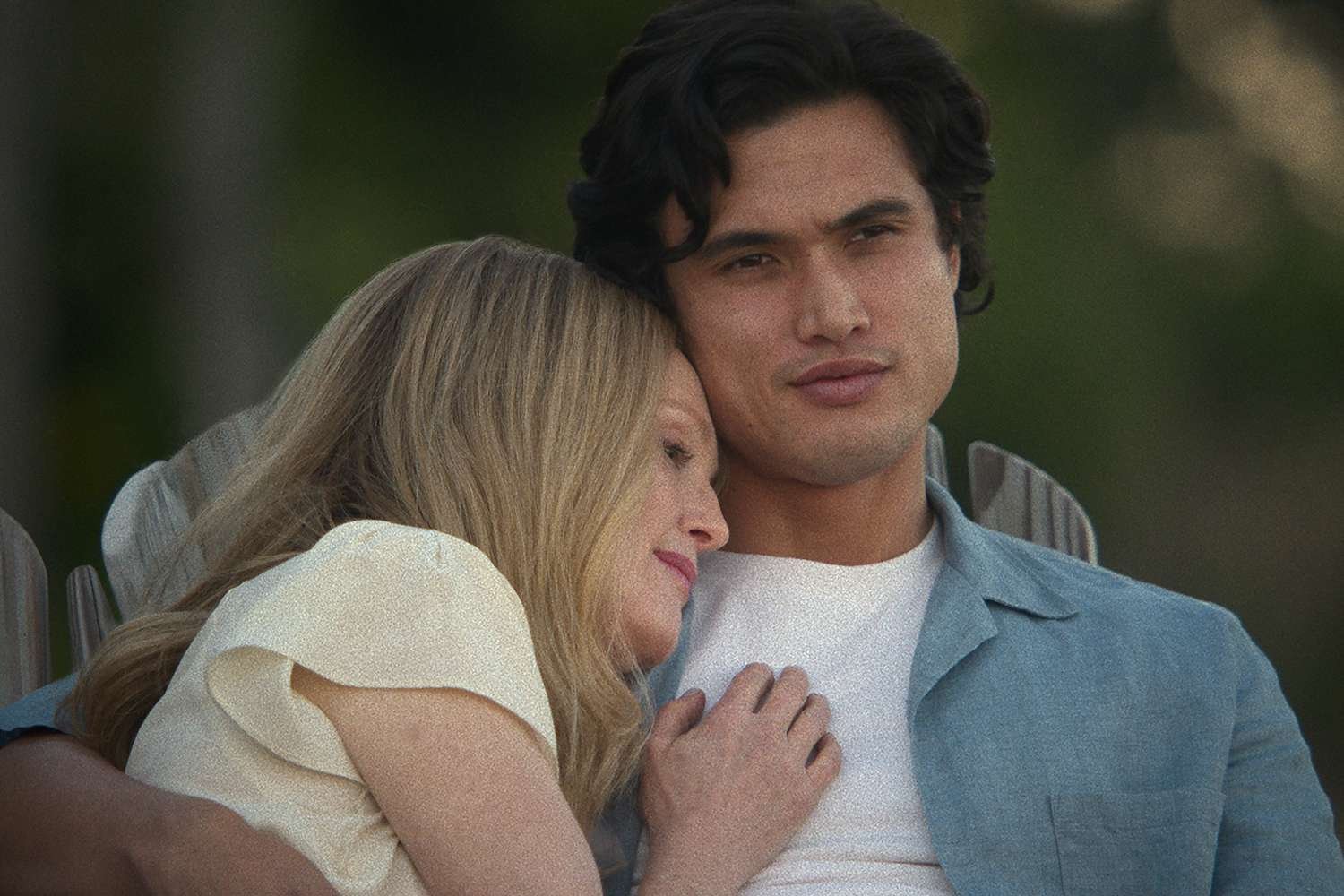

Natalie Portman and Julianne Moore in May December

Last week, my friend Ella and I saw each other for the first time in over a year. She came over for dinner and we spent three hours on my couch exchanging stories about what had happened in the interim. Ella famously “can’t do text,” a virtue I cannot but respect as a serial paragraph-sender, so we end up eccentrically monologuing during reunions. The way we self-narrate cracks us up; we share a similar quippy, hyper-specific vernacular that allows for image-to-image clarity for the listener. At one point deep into the hang, Ella was approaching the peak of a turbulent, twenty-minute story when she said something to the effect of, “and in that moment, I knew I would be dealing with this for months to come.” We paused and laughed, because of course at that moment she didn’t really know. By the time the story had reached my ears, it had been mulled over in Ella’s head and tested countless times on other close confidantes. I was getting a version two months out, embellished with Ella’s refreshing comedic timing and cosmic revelations. Yes, we both confirmed, our stories change a little each time we tell them. But as we get further from their happenstance, can we get closer to the emotional truth?

This conversation made me think of Todd Haynes’ new film May December, which is about the revisiting of a public scandal some twenty-odd years after its tabloid prime. The film, which I would describe off the cuff as if Almodóvar directed TÁR, follows the beautiful and talented actress Elizabeth Berry (Natalie Portman), who arrives in Savannah, Georgia for research on an upcoming film. She will play the real-life figure Gracie Atherton-Yoo (Julianne Moore), a woman who, at the age of 36, had an affair with a twelve-year-old boy, a case that captured international media attention. Gracie is married to Joe (Charle Melton), who is now 36, living in a secluded island community with their (yes, their) three children. As Elizabeth immerses herself into Gracie and Joe’s home life, we begin to realize that neither woman is as she seems, both selfish weavers of a faulty self-narrative.

May December is not simply about the story of Gracie and Joe, but rather who is telling it and how. Haynes himself, as a distinguished filmmaker, is a contender. The movie begins with an earworm: a terrifying blare of music that’s so sudden I felt sitting in the Francesca Beale Theater that someone had reached through the screen and slapped me. The score, Marcelo Zarvos’ reorchestration of the theme from The Go-Between (1971), pervades the movie from the get-go. From the moment we hear the first “DA-DUMMM!” (go listen, there is seriously no other way to describe it), we immediately understand the film as a melodrama, participating in the soap opera tradition in a way that is unsettlingly humorous and necessarily misleading.

In Gracie’s first scene, we see her in the kitchen, preparing for an afternoon barbecue. She opens the refrigerator solemnly and stares into it as the camera comically whip-zooms in on her face while the score abruptly plays. “I don’t think we have enough hotdogs,” she says. We then cut to a grill lined with hotdogs. My theater burst out laughing. I was writhing in delight, in disbelief at how funny it was. In this quick moment, Haynes teaches us how to watch the movie, positioning the viewer as a sort of detective figure like Elizabeth. We are meant to examine Gracie and Joe with extreme scrutiny, he tells us. Why? Because nobody –especially those who insist upon it– is to be trusted.

Right away, Haynes draws our attention to the construction of false truths and realities that occur in both the public and individual imagination. In a Q&A following a screening, he calls the score stinger “a warning bell. It’s telling you to watch out because some things headed your way are not what they seem.” There are countless moments like this throughout the film. Every time you think music’s going to play, it does. You come to expect it. In this way, May December elicits a sense of déjà vu; I felt as though I’d seen it before. Not because it was derivative, but rather, I felt I had told the story before, in this exact gossipy fashion. By mimicking the very ways we have been conditioned to consume complex stories through the media, Haynes introduces a meta-irony twinged with sadness.

In one scene, Joe and his son smoke weed on their roof. He gets too high and cries, struggling to give his son words of wisdom before his high school graduation. “God, I can’t tell if we’re connecting or if I’m creating a bad memory for you in real-time,” he admits. The line comes off as humorous due to the circumstances, but is unmistakeably melancholic and human– it is impossible to know the true effect of our words and actions in any given moment. How is memory created “in real time,” in the private and public realms? We can’t know until it’s passed.

Hindsight, while a privilege, can be dangerous. In a review for Vulture, Ebiri calls May December “a booby trap of a movie. It’s designed to pull you in multiple directions at once…it makes you feel one thing, and then makes you wonder if you should be feeling something entirely different instead.” These multiple directions are what Haynes might call “the language of modernist cinema,” where the tools of the medium –music, cinematography, editing– are placed overtly in the foreground, and in Haynes’ case, are dissonant with the subject matter. Why is it that we are cackling at this woman who, twenty years ago, committed an illegal and amoral act? Is it because she has an outrageous lisp, arranges flowers, and bakes cakes for neighbors who place their orders out of pity? Because the way she is framed leads us to believe she is a complete joke? Maybe so, until the latter half of the film when we consider the irreversible damages done to Joe.

Haynes views Joe as “someone who is locked into a choice that he thinks is his. He then realizes that these choices have been made on his behalf. He’s the only character that you feel is truly capable of change.” In a pivotal confrontation scene, Gracie repeatedly asks Joe, “Who was in charge?” It’s an evil form of gaslighting and emotional manipulation that has, as it turns out, been her trick all along. Joe, clearly psychologically stunted at the age he met Gracie (Melton’s physique in the film is pointedly cherubic), wonders for the first time if the person in charge wasn’t himself. The movie, replete with its warning bells and punctuated transitions, reminds us that we have no such language for interpretation in everyday life. In retrospect, we find difficulty in believing the bells weren’t always sounding. Maybe they were, but we just couldn’t hear them.

Of course, Haynes never abandons us in tragedy. The film’s visual motif of butterflies raised by Joe emerging from their cocoons seems saccharine on the surface, but it’s an apt metaphor for how we as storytellers by nature can rewrite and revisit our narratives like Ella and me seeking joy and healing in the shaping of our melodramatic anecdotes. It’s easy to feel locked into a certain mode of thought or creation, as the path laid by our predecessors appears so final and sacrosanct.

But remember, even the very medium of film is slippery and incompatible with imitation. Elizabeth –in my opinion the real tragic figure in May December– breaks down on set, unable to “find” the character of Gracie. She begs the director for multiple takes, claiming that “it’s getting more real,” but really she is copying, deriving, and wholly self-absorbed. Getting closer to the truth, Haynes tells us, is not a matter of what tools we use to get there, but how we use them, and with what intentions. Do we aim to hurt? Honor? Heal? Whatever it is, we’d better take a good, hard look in the mirror first.

P.S. Recommendations: A great interview between brilliant minds David Sedaris and Jodie Foster & an insightful Vanity Fair Gerwig profile.